Alex remembers... THE CRASH OF '87

The stock market crash, which began in New York on Friday October 16th 1987, took the City of London by surprise. For a start there was almost no one at their desks. The Great Storm which happened on the Thursday night had brought transport chaos to Southern England and hardly anyone had managed to make it into work. Those few who had showed a Dunkirk Spirit and braved the epic journey by car, bicycle or on foot, weaving around fallen trees, found the City a ghost town.

A strange Saturnalia reigned. The senior people, who tended to live in the country, hadn’t been able to get in. There was no internet in those days, few mobile phones, many of the telephone lines were down and many houses without power, so the bosses were isolated and had no real idea what was going on. The juniors, who tended to live in London, were in charge. And they hadn’t a clue what to do. Luckily for them the Stock Exchange decided to close the market at lunchtime, due to the absence of personnel (the only time this has happened in living memory - markets remained open even on 9/11). So everyone just slipped off for a long lunch. A few market makers repaired to their local pub or wine bar and made prices on the back of beermats. Back in those days of “my word is my bond” they would be expected to honour these deals when markets opened again on the Monday. It was a throwback to the beginnings of the City in Edward Lloyd’s coffee house (compliance would never allow it today). After a bottle or two of claret most people set off early on the long return journey home.

They got home to find that Wall Street was off by 109 points (a trifle by today’s standards, but a significant correction back then) and began to be fearful of what Monday would bring.

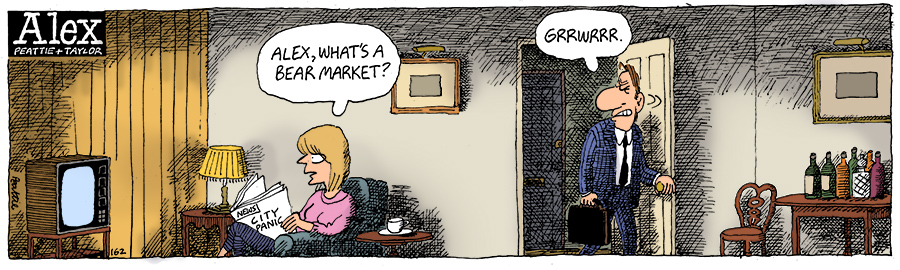

After a tense weekend spent trying extract fallen trees from their Porsches many City people were back at their desks by 5am on the morning of what would come to be known as Black Monday. Asian markets had crashed overnight in response to Wall Street’s sell off on Friday and the wave of selling predictably enveloped the City. Sensible people realised that it was a buying opportunity for blue chip stocks. But most people weren’t sensible and just sold everything. The TOPIC screens were a sea of red. To Alex’s generation it was like a scene from Trading Places, except it was actually happening.

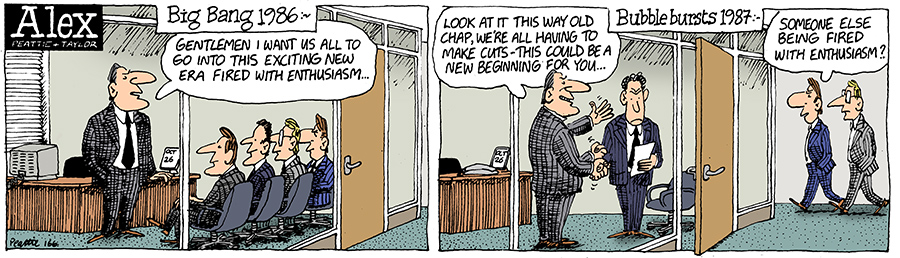

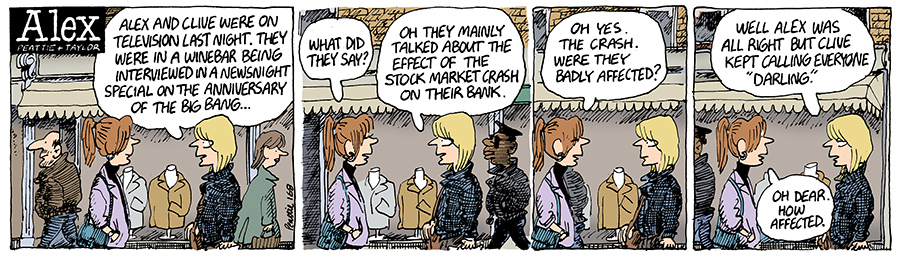

"Big Bang” - the deregulation of financial markets - had occurred just a year previously Traditional British stockbrokers and jobbing firms had been bought up by megalithic American banks. Many of the partners of the old-school City businesses had decided to take the silly money that was on offer and retire. The Americans recruited heavily from the whippersnappers of Alex’s generation. The problem was that none of these youngsters had any experience of trading a bear market. Alex was a typical example - a wet behind the ears Yuppie, a little over six months into his first job, who had no idea that share prices could do down as well as up.

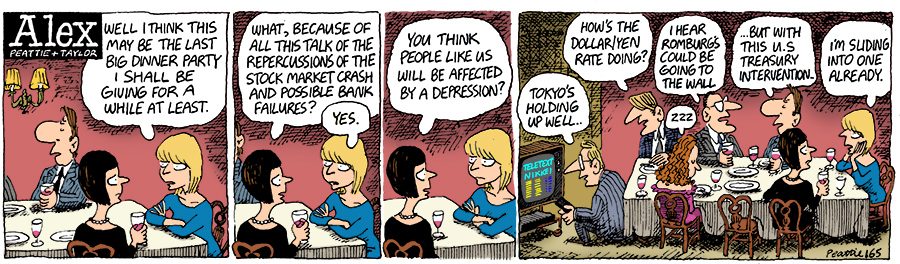

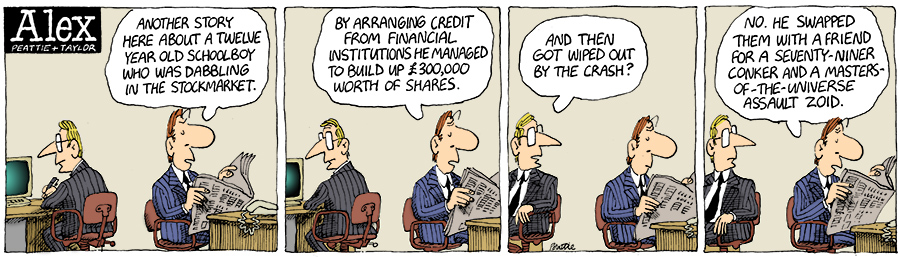

This was also the era of the Thatcherite privatisations, where plumbers, taxi drivers and even schoolchildren had gorged themselves on the pickings from the BT and British Gas flotations and were fully invested in the markets. When the Crash came they couldn’t make their margin calls and got wiped out. In that compliance-lite age no one had bothered to do the due diligence to check their creditworthiness.

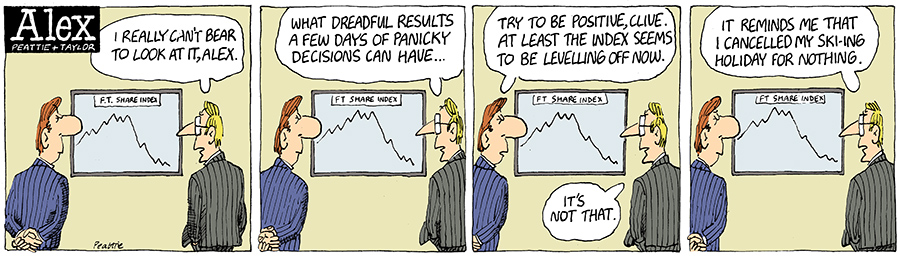

The baton of global panic was passed back to Wall Street and it duly collapsed on Monday, ending up 508 points down (a record at the time). The FTSE had lost over 300 points by the close of trading. The City responded in typically British fashion by coining jokes: “What’s the difference between a Yuppie and a pigeon? A pigeon can still put a deposit on a Porsche”. “Did you hear that Pedigree Chum has gone bust? Yes, they had to call in the retrievers.. “ These jokes would be duly trotted out again in each subsequent market downturn.

On Tuesday there was a “dead cat bounce”. Prices unexpectedly recovered, before collapsing again, which caught a lot of people out who had bought into the rally, thinking it was a recovery and caused further big losses on trading positions.

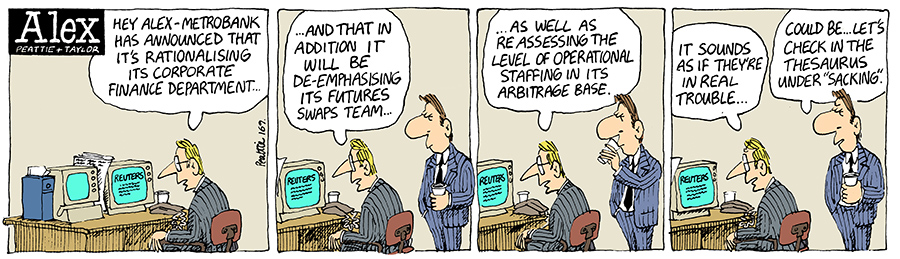

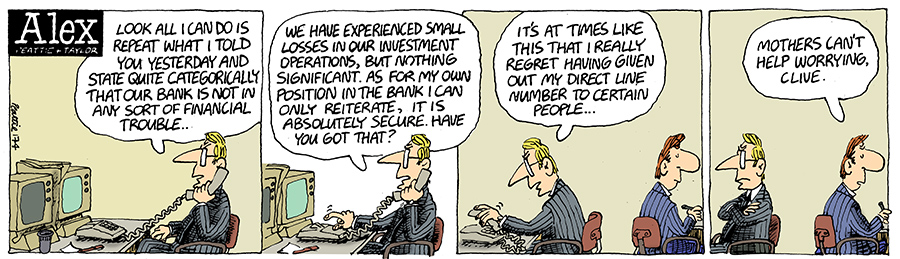

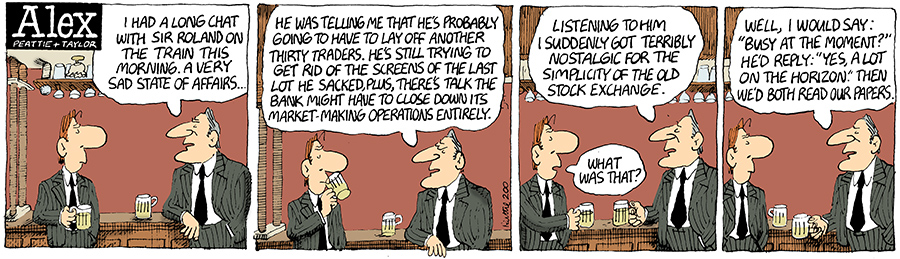

President Reagan breezily described it as a “correction”. The City wasn’t so sure. One senior banker pronounced solemnly at morning meeting: “The party is over.” Of course it wasn’t. There was a big shake out in merchant banks in the Square Mile, but markets recovered fairly quickly and had made up all their losses within two years.

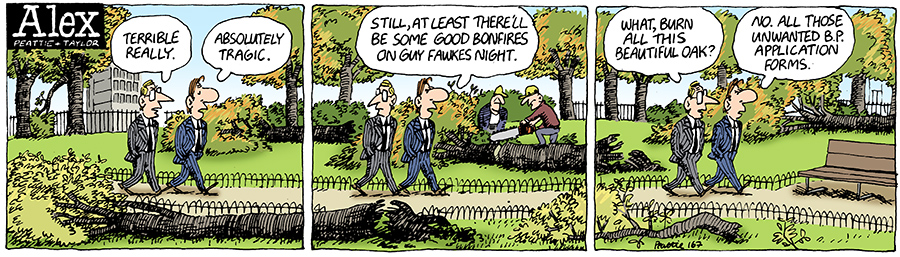

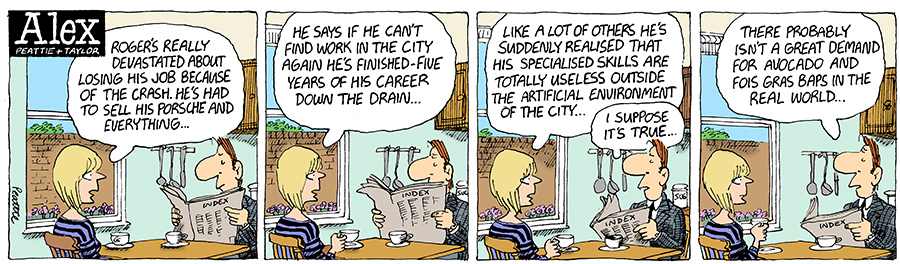

In retrospect the Crash of 87 was just a barely perceptible blip on a stock market chart that has since soared by 6,000 points. There were painful short-term consequences for the Yuppies of course. For a start that autumn’s grouse shoots had to be cancelled due to all the storm damage. And quite a few of them lost their jobs. But for Alex’s generation it was their blooding. Those who survived the knee-jerk downsizing in merchant banks had proved their mettle. Thirty years on, Alex still talks about it proudly; but not too loudly, in case anyone thinks he is a dinosaur.

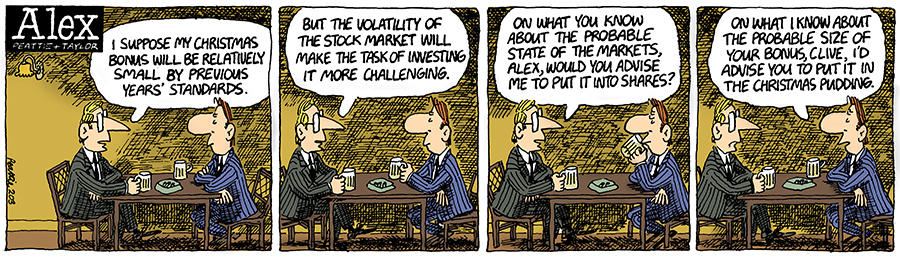

As for us, his creators, we found ourselves having to evolve a new type of joke. Like Alex, we had only been in the job just over six months. Up to this point most of our cartoons had been about Alex being a cocky, insensitive, materialistic swine. Now he and his ilk found themselves forced into an unfamiliar humility as they were suddenly fearful of losing their bonuses and their jobs and were facing a public backlash against bankers. The Crash ushered in the first of the many redundancy jokes that would subsequently become a regular feature in the strip and ultimately paved the way for the compliance gags (as the authorities belatedly tried to bolt the stable door) which in today’s heavily-regulated financial world are now a staple of the cartoon.