About > The Creators > Peattie + Taylor

Charles and Russell: The early years

Alex the comic strip started in February 1987 in the London Daily News, the Bob Maxwell-funded newspaper that was designed to be a rival to the London Evening Standard.

The previous year Charles had walked in (more or less off the street) to the new journal’s offices, where the staff were working towards the launch. The Features Editor (Nigel Horne), politely dismissed the ideas in Charles’ portfolio but suggested that there might be room in the paper for a new strip if it was more London- themed (and he also liked ‘Doonesbury’ and ‘Bristow’). Charles agreed to come back with something else in two weeks’ time.

This was the 80’s when security was more lax and people could still walk in off the street into organisations like newspapers, design agencies and even banks (and onto their trading floors to sell sandwiches and shirts or do shoe shines).

These days of course it could never happen like this anyway. The job of finding a new comic strip would be tasked to a panel of editorial and creative marketing executives, in-house, who would brainstorm round a table, devising exactly what kind of strip they needed, what characters should be in it, what they should look like, plus intricate details of their personalities, demographics and lifestyles, to accord with the innermost aspirations of their readers. Once this had been accomplished the executives would think up exactly what kind of cartoonist they might need to draw their new feature out and to think up the actual ‘jokes’; this would be a matter of painstakingly refining and redefining the qualities of what their perfect cartoonist candidate should be like, for example: “So: someone a bit like Steve Bell or Quentin Blake, but a woman and preferably younger and maybe less political, and more edgy…?”

Then they’d look out of the window of their office and hope to catch sight of that person waiting outside in the street, so that they could commission him/her to work up their ideas for free (and make them ‘funny’).

Subsequently they would plan to show these drawings to a focus group… Hrrrmph… Anyway…

Charles was working with Mark Warren back then, and they started by trying to do a strip about a London taxi driver. When this turned out to be a dud they attempted to create an ‘ensemble’ strip about four different young people living in a house: An idealistic political one, a wannabe famous one, a yuppie and a central everyman-ish character who they couldn’t agree on a job for (teacher? architect? builder?). Because the yuppie had all the best lines and since there were only two weeks before they had to get back to the newspaper with a proposal, they went with him as their protagonist and called him ‘Alec’, (like ‘Smart Alec’). It was very unformed. Just a banker with a big nose really.

Then Mark got offered a solid job in an advertising agency as a copywriter and took it.

So Charles began looking for another writing collaborator. He was being sent examples of work by contenders and he was feeling more and more uncomfortable, hemmed-in and unreasonably picky with each candidate he turned down. (Sample joke: Alex, about an acquaintance: “He’s something big in the City.” Penny’s reply: “What, like a lamp post?”). Then he was introduced to Russell at a Christmas party in the upstairs office of the advertising magazine Design Art & Direction. Russell was working as a freelance journalist for the magazine, writing articles about advertising executives. A mutual friend had mentioned that Charles was looking for a co-writer and Russell pitched his services.

Rather than actually risk committing to a full-on meeting later, with all the embarrassment of rejection, recrimination and queasy, failed bonding that was likely to ensue, Charles sent over a batch of crumpled rough strips the next day which he had drawn out already and asked Russell to look at them and to have a go at writing a few more in the same vein, if he felt like it.

It was about a month before the London Daily News was scheduled to launch (its third delayed launch date).

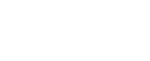

As there wasn’t much time to talk about the character of Alec, they decided not to. Instead they had a rule that any facet of Alec’s personality or life should be illustrated with a strip that one of them would be obliged to draw out and show the other, rather than be waffled about verbally. There was also a rule that ‘thoughts bubbles’ were banned, so one should only find out what a character was thinking by their actions or their words. This latter rule has been relaxed in recent years to allow a ‘visual’ to appear in a thoughts bubble sometimes and very occasionally a ‘swear word’, but otherwise, these rules still stand.

Alec had already been defined as a post- Big Bang City boy, which was a new social stereotype. Charles had been reading “Money” by Martin Amis and the “Flashman” series of stories by George MacDonald Fraser. Both had amoral heroes. Charles and Russell discussed the idea of humanising Alec by giving him frailties and vulnerabilities such as being inept with women. But they threw such ideas out quickly. Alec was imagined as an unapologetic winner, which was in contrast to the fashion at the time for British ‘lovable loser’ comedy characters (a role which has subsequently fallen to Alex’s colleague Clive).

One final change, the day before the first edition of the paper – but not before the dummy first edition - was forced by the discovery that there was already a comic strip character called Alec. This is why it was changed to ‘Alex’ at last minute and published as such the next day: February 24th 1987. The creators thought the strip would probably last for between six months and a year.

Charles and Russell have often been asked whether either of them has worked in the City. The answer is ‘No’. Charles had been a reasonably successful portrait painter and after that, a jobbing cartoonist, illustrator and designer of greetings cards. Russell was a freelance journalist with a background in Russian. Their early attempts at satirising the financial community were based on blithe ignorance and puns on words like “bond” and “gilt”. But they were both in their twenties, living in London and they knew a few people who had gone into the City at the time of Big Bang in 1986 , which helped give them an idea of the attitude. Russell’s childhood friend Colin and Charles’ younger brother James were both inadvertent inspirations.

This on-going contact between the satirists and their subject matter has been fruitful over the years. Readers began coming around to the cartoonists’ office in Docklands (a room in a design company’s premises in those days) to pick up their originals, often stayed for a drink and would put the cartoonists right about who Alex really was, what he did all day, where he would have gone to school, where he ate out, what kind of car he’d be driving, even details about his family background (“No, no, no… I’ll tell you what his parents are like…”) when the cartoonists had only the haziest of ideas. Some of the readers (clients? customers? targets of satire?) would become regular ‘moles’. A few of them are still lunching with the creators to this day.

In the early days (in their Docklands office and later in another one in the rag trade area of North Soho, aka ‘Noho’, aka ‘not really in Soho’) Charles and Russell sat at a desk together with a clock between them. Then they took a subject and gave themselves twenty minutes to come up with something funny about it (often failing for hours on end). The rule was still that if either of them had an idea for a strip they had to draw it out in rough and show it to the other, rather than tell it. Then the rough strips were put up on a board to be decided upon, re-scripted and so on later.

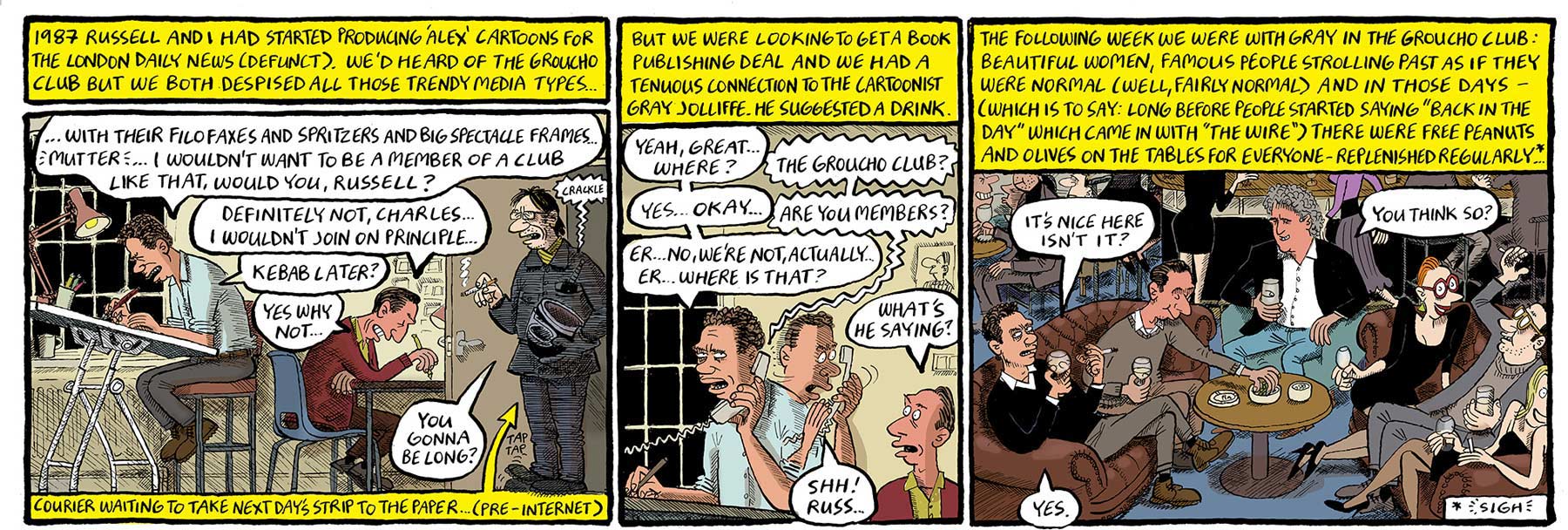

Occasionally they would be unable to come up with a serviceable idea until about mid-afternoon (sometimes later) and Charles would then have to rush to his drawing desk to draw it out in time for the next day’s edition. The motorcycle courier would arrive from the newspaper to pick up the artwork (there was no email in those days, any Millennials reading this) at about 7pm. Sometimes it still wouldn’t be ready and Russell would have to stall him with offers of cups of tea.

Within a couple of years the cartoon been taken up by several overseas papers (eg the Australian Financial Review and The New Zealand Herald) who had to be sent weekly packages of cartoons. Back in those dark days before the invention of digital scanners this involved making a PMT (a type of photographic reproduction process) of each cartoon on a huge clunky contraption in a dark room. This was frequently Russell’s job. These prints then had to be sent by old-fashioned mail to the various countries. In the case of New Zealand, it turned out that the costs of actually sending them out were not even covered by the fee. Today the syndication cartoons are uploaded to an ftp site in a matter of a few seconds. Somehow much less romantic. But at least it makes money.

After a few years they found that they quite often used to each come up with the same idea for a joke from the same bit of information or subject matter. After ten years Russell was doing more of the jokes than Charles, while he was the one who still had to draw them out. People usually want to know “Who does the writing and who does the drawing?”, but actually the interesting stuff happens in the overlap. They both have ideas for jokes. Russell writes more and writes more of the City-based jokes. He is the one with the arduous job of lunching with bankers in agreeable restaurants to get the inside track information. Then they both rewrite each other’s material, intensively. Charles always draws, but finds Russell’s visuals on his rough strips influences how he does it.

Since the coming of the internet, they found they no longer needed to be in an office together. Since 2001 they have both worked mainly at home, sending roughs and artwork to each other down the line and then talking by phone. The process of doing it by the clock still happens when a major subject breaks in the news.

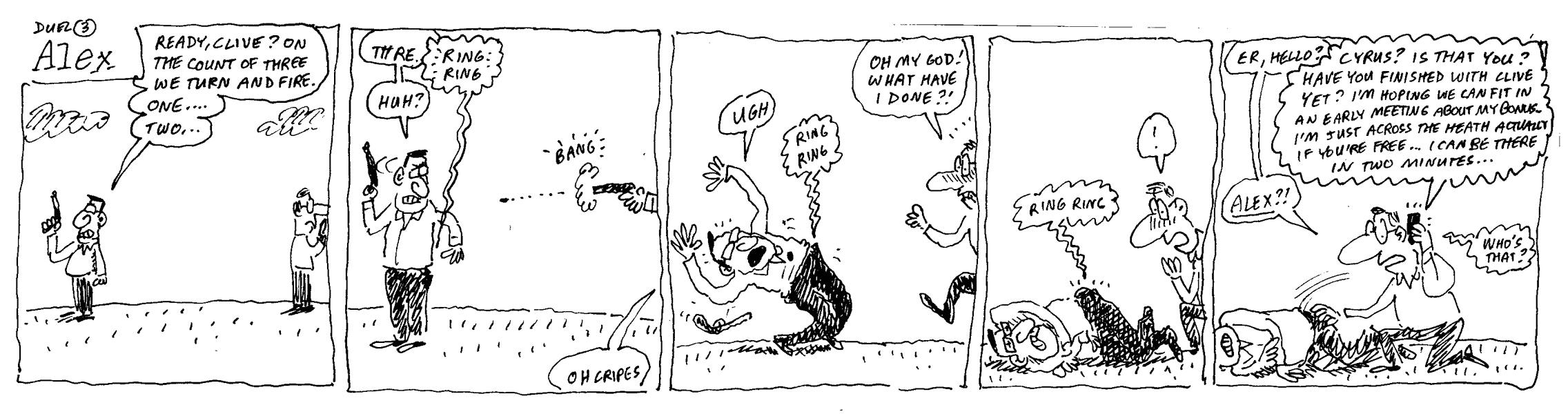

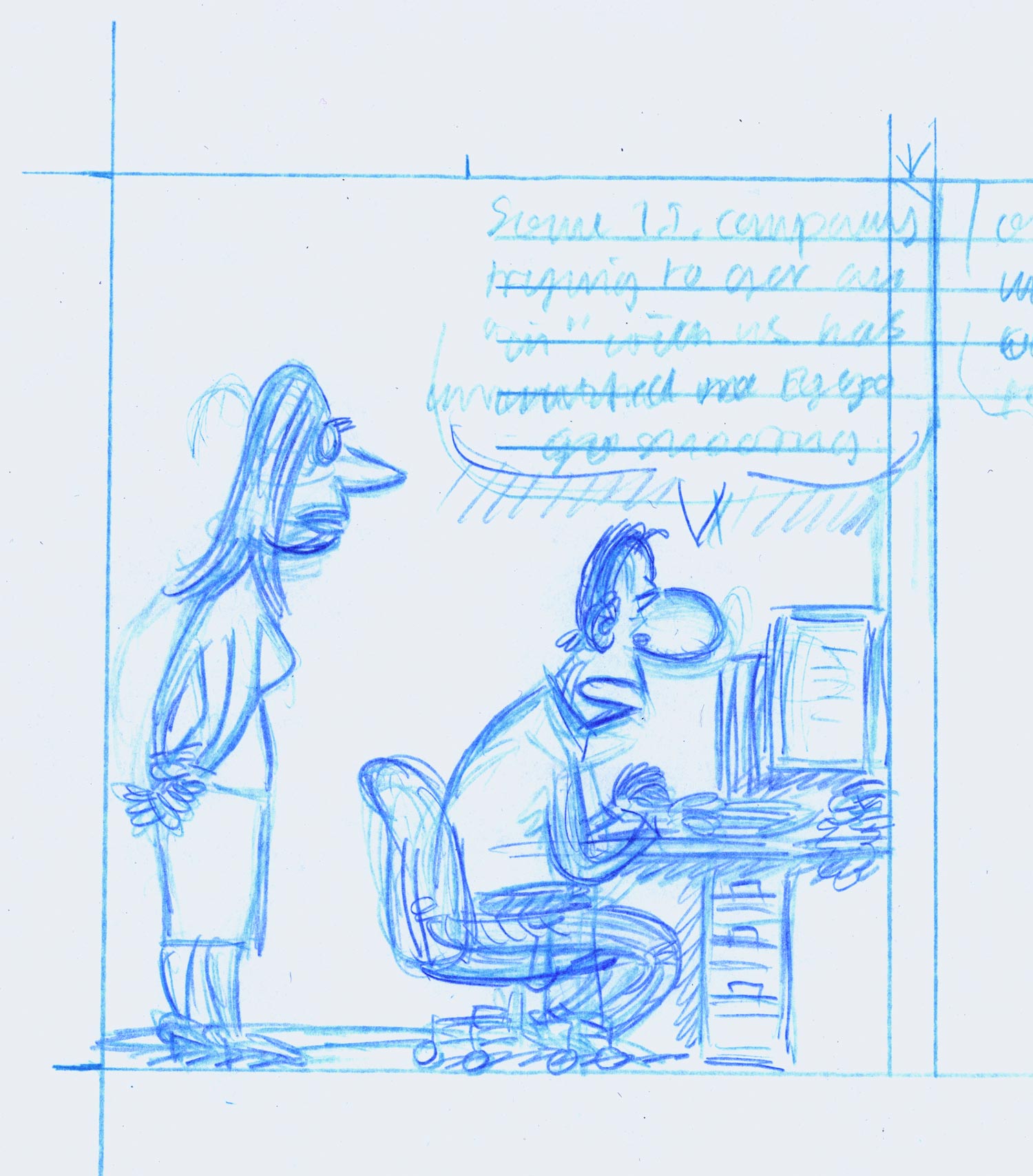

This is what their rough jokes look like:

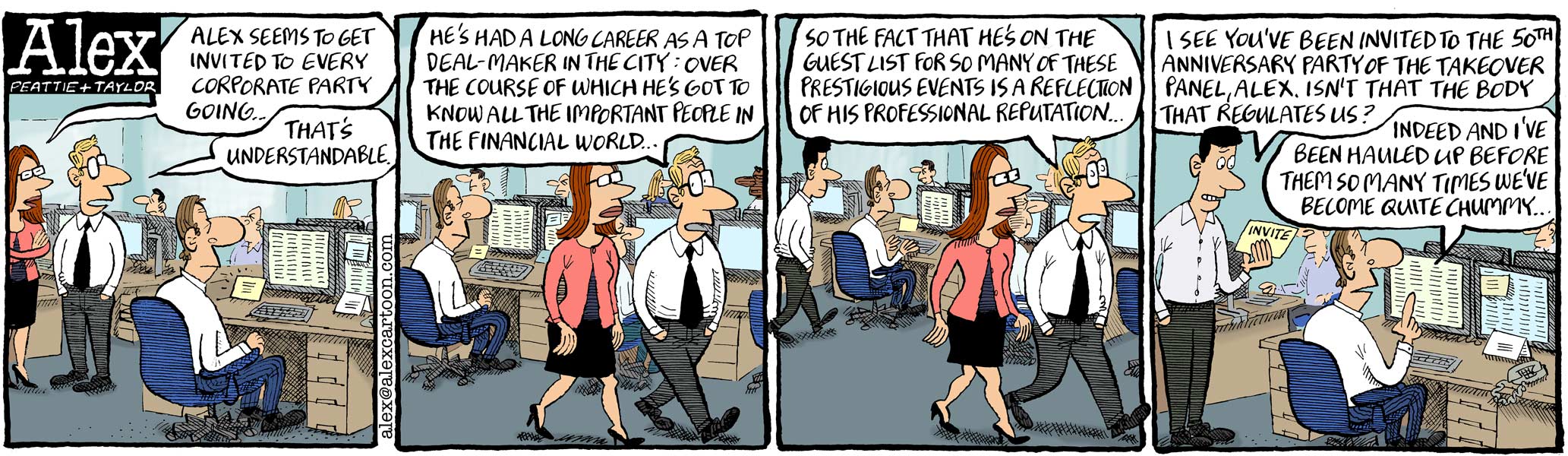

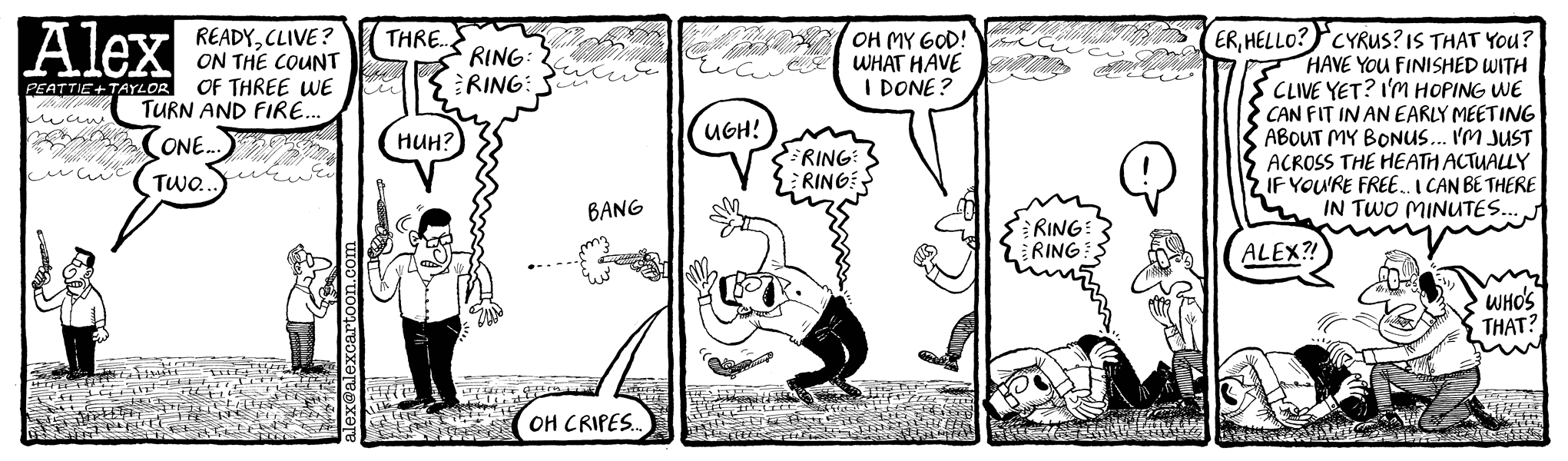

This is what they look like inked in:

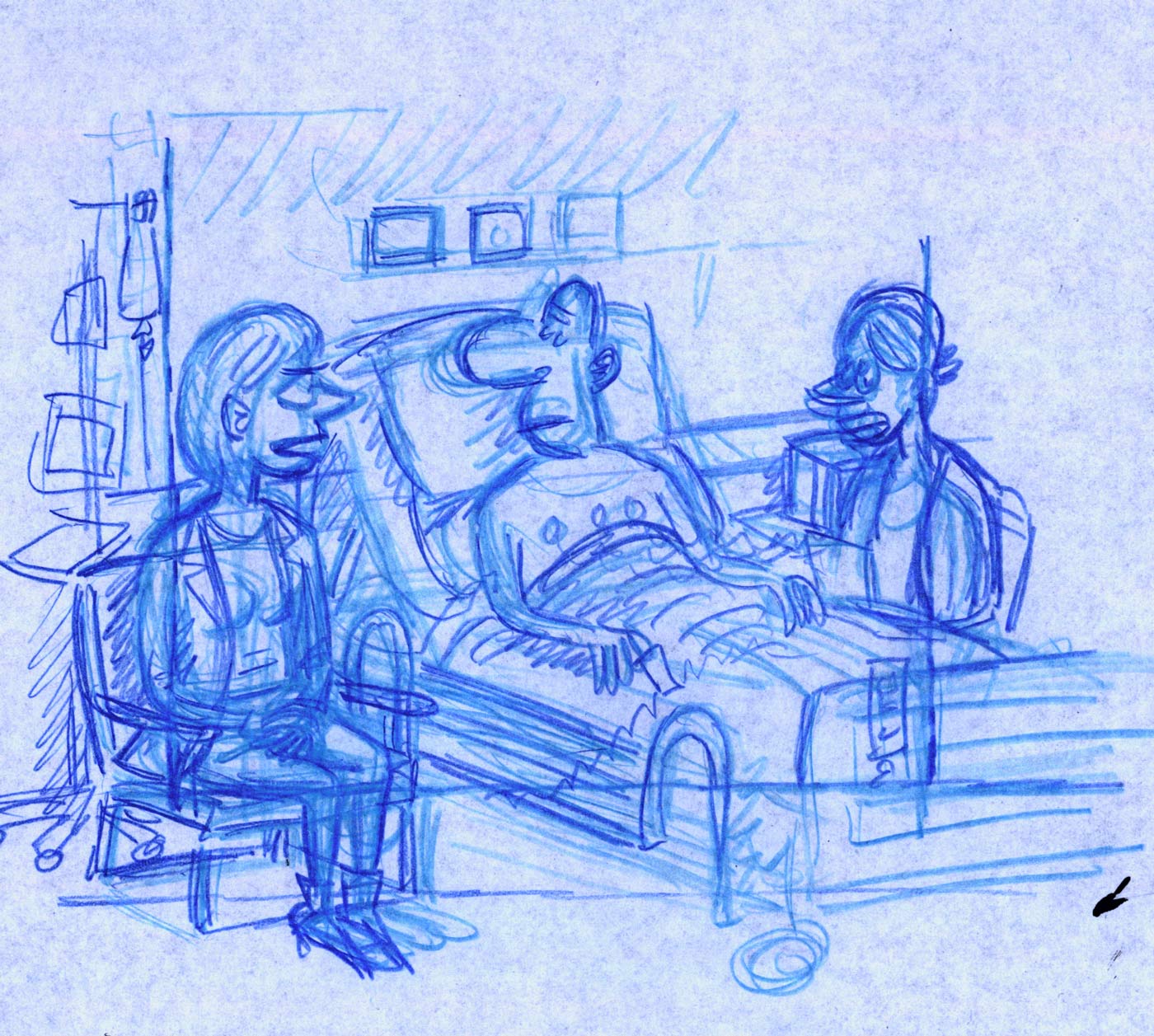

This is what Charles’ drawings look like when they are penciled out

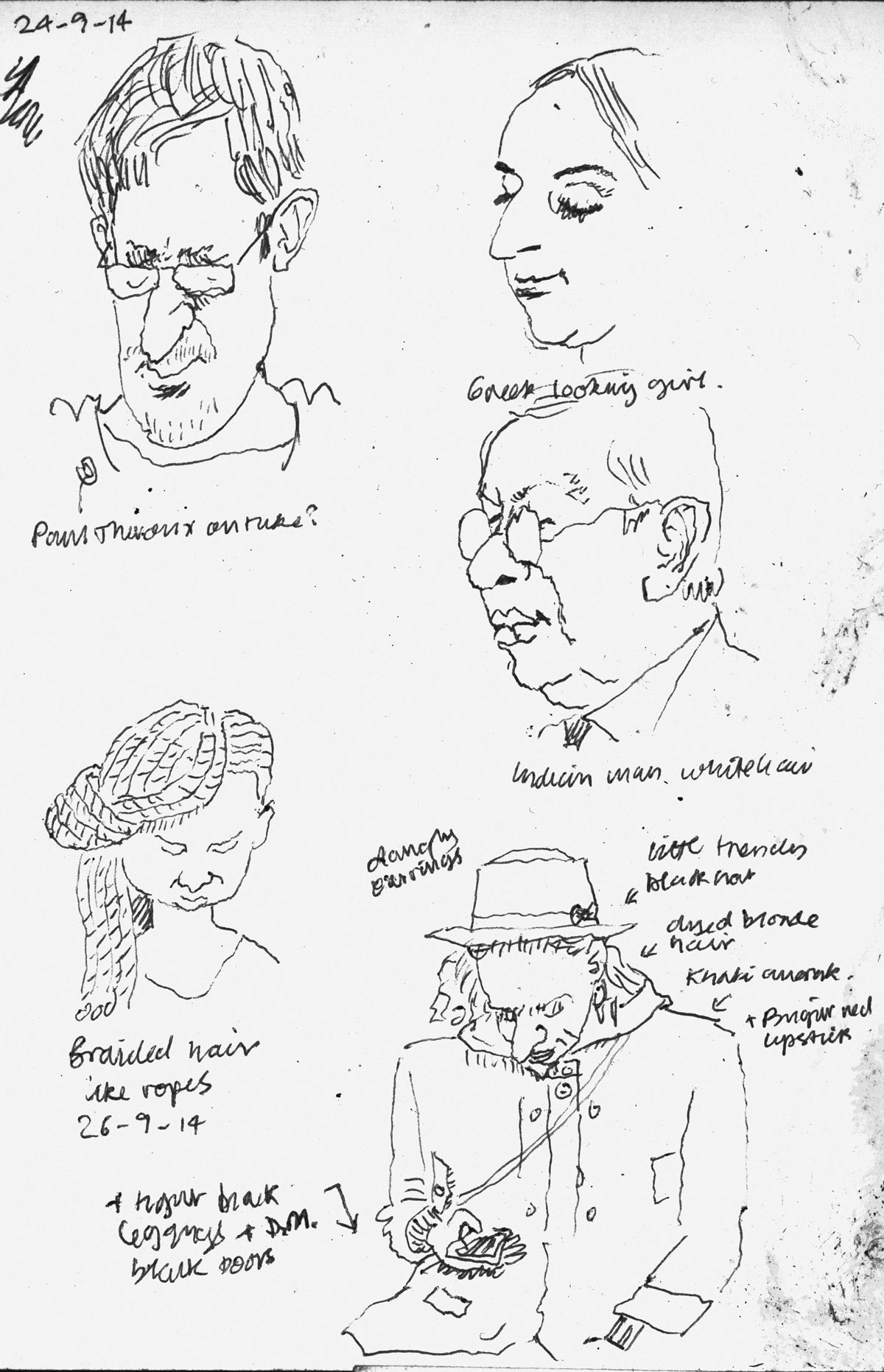

Although camera phones and search engines make picture research much easier these days, Charles still carries a small notebook or blank post cards at all times to sketch details of locations or how people look, which he keeps in a card index. These are typical:

He also still inks with an old fashioned mapping pen and ink, but uses a digital stylus and tablet for clean-up. Colour these days is added digitally.

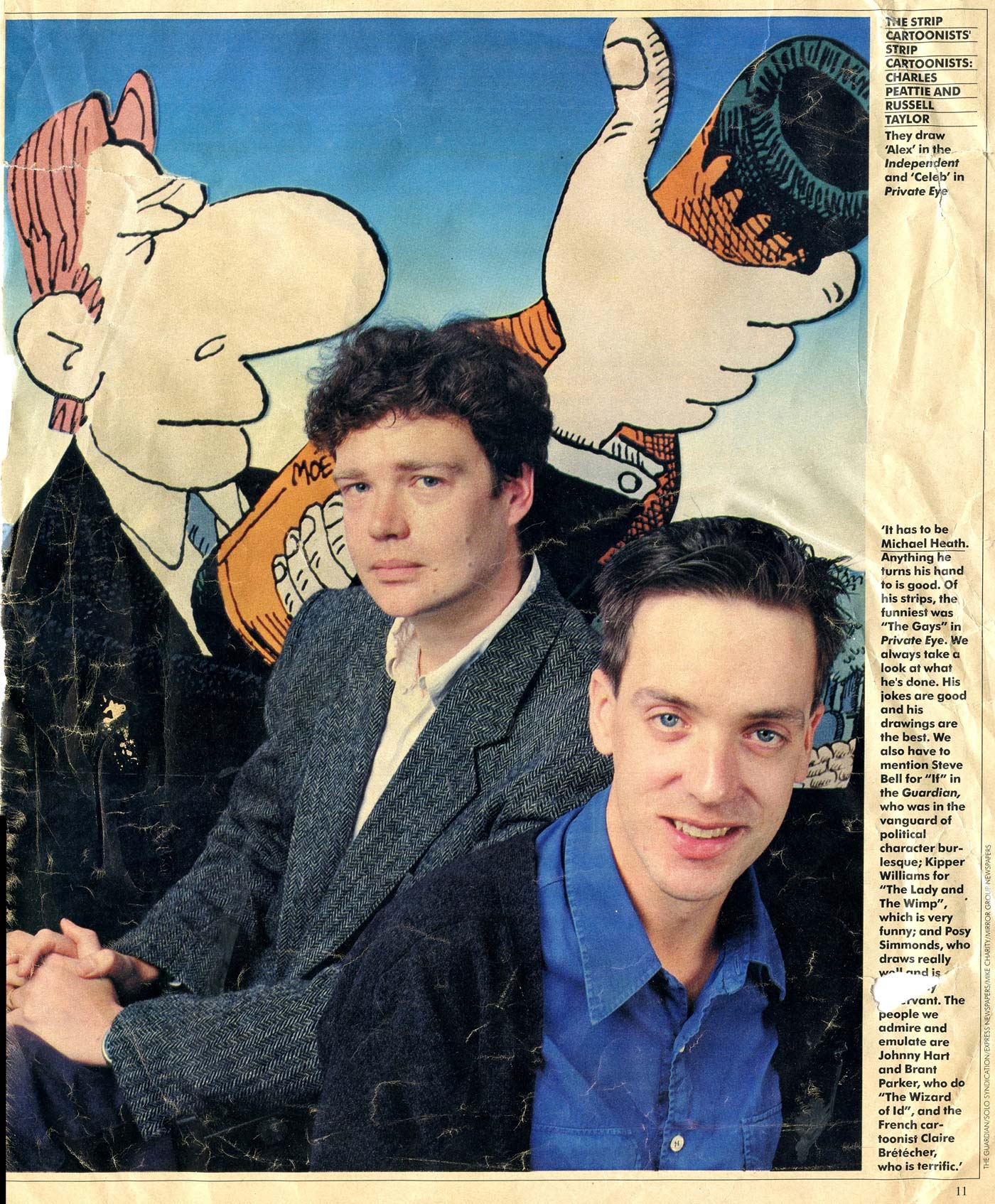

Here are Peattie and Taylor, early in their career, just chosen by their peers as ‘The comic strip cartoonist’s cartoonist’ in "The Observer", slightly embarrassingly, given that the creator of the enormously successful strip ‘Andy Capp’, Reg Smythe, was up for it too.

This is them with the ir cartooning colleague at the “Telegraph” Matt at a cartoon awards’ ceremony.

With Eleanor Lloyd, co-producer of the Alex play at the first night party in 2007.

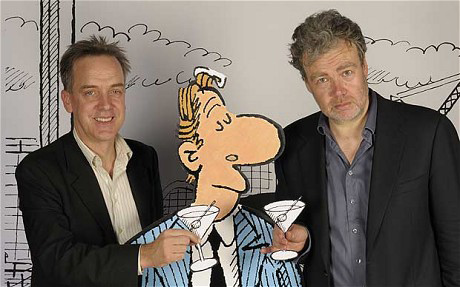

At a party celebrating Alex’s first twenty five years.

Recently, December 2017, signing books in Harry’s Bar in The City.

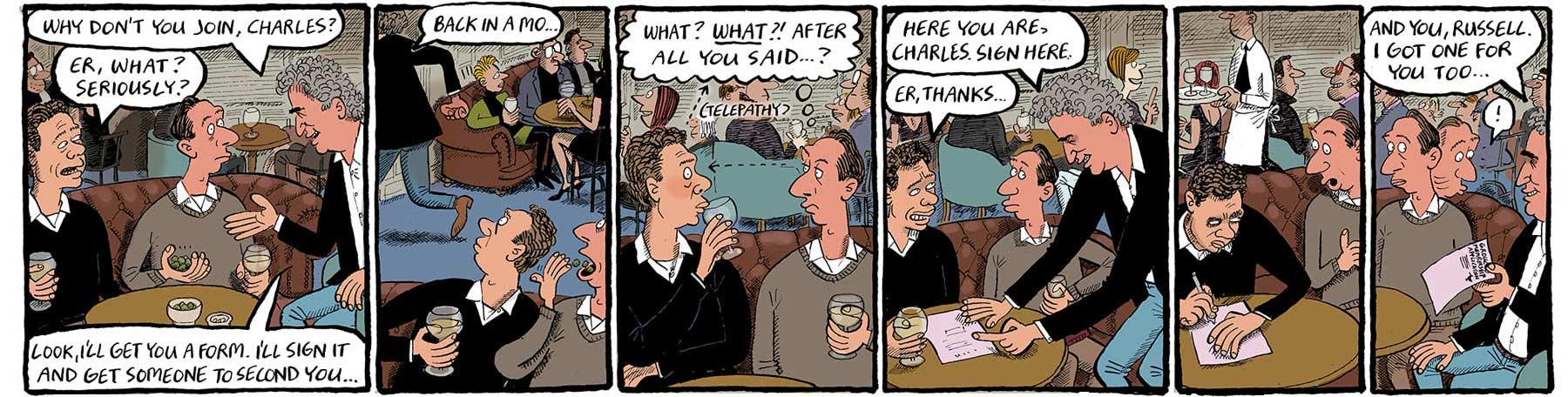

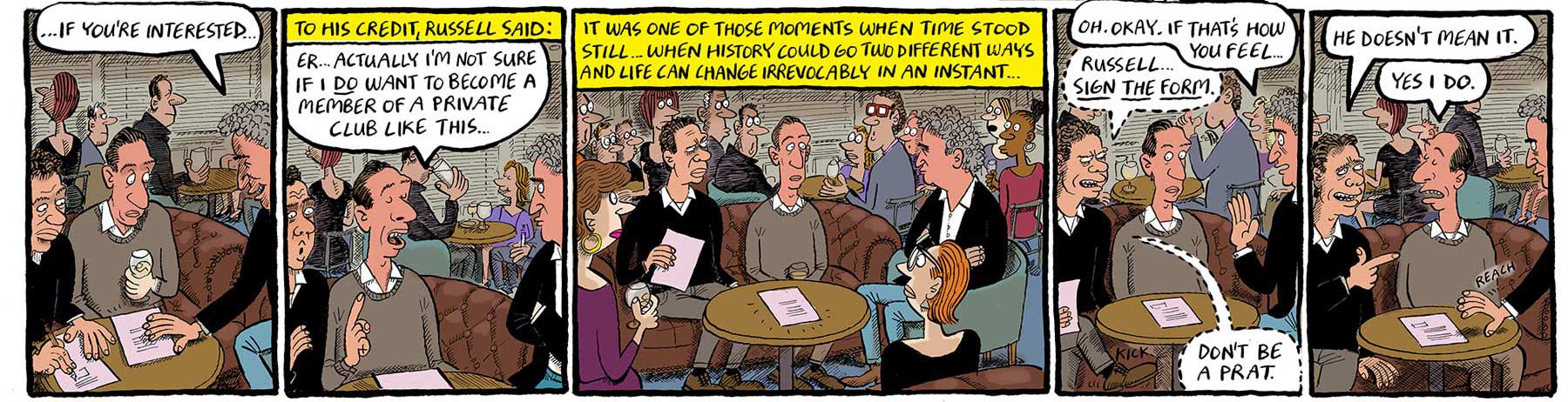

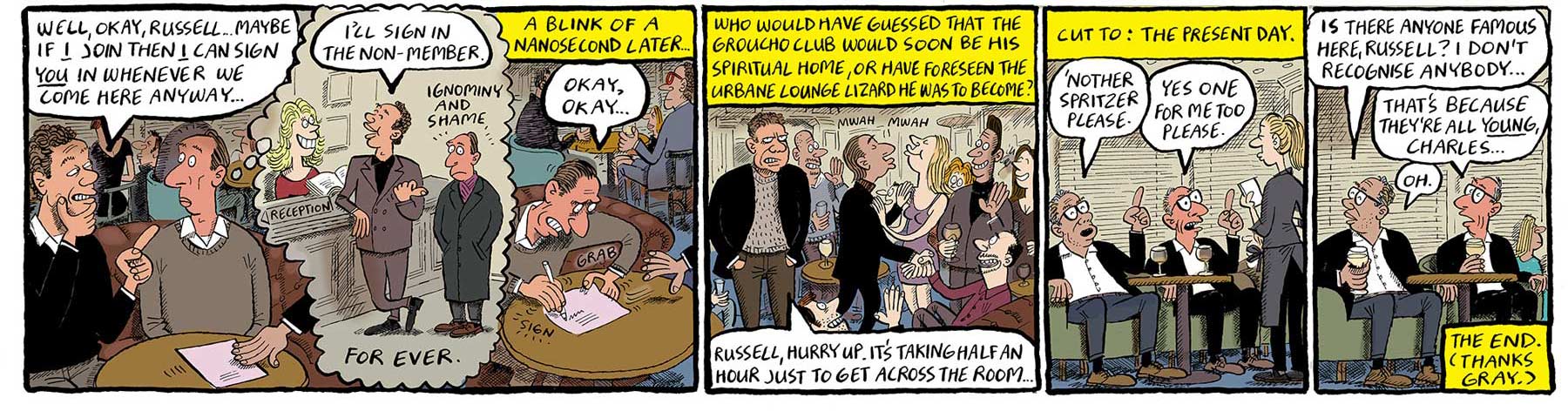

This is the story of them both joining the Groucho Club, which seems to encapsulate a lot about their 30 year collaboration…